Price doesn’t always equal quality

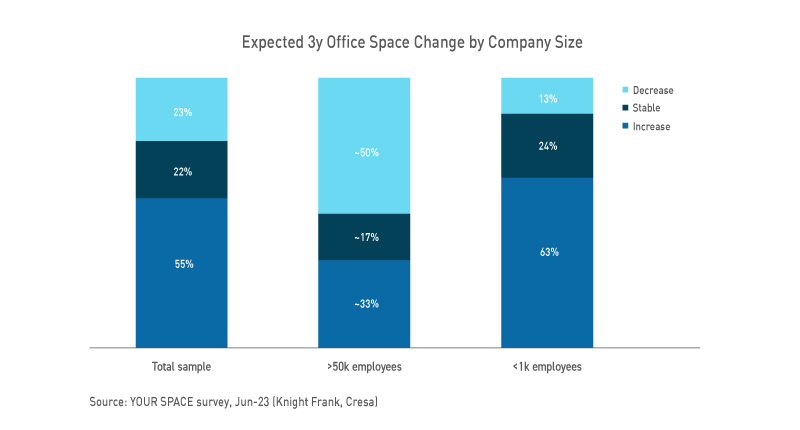

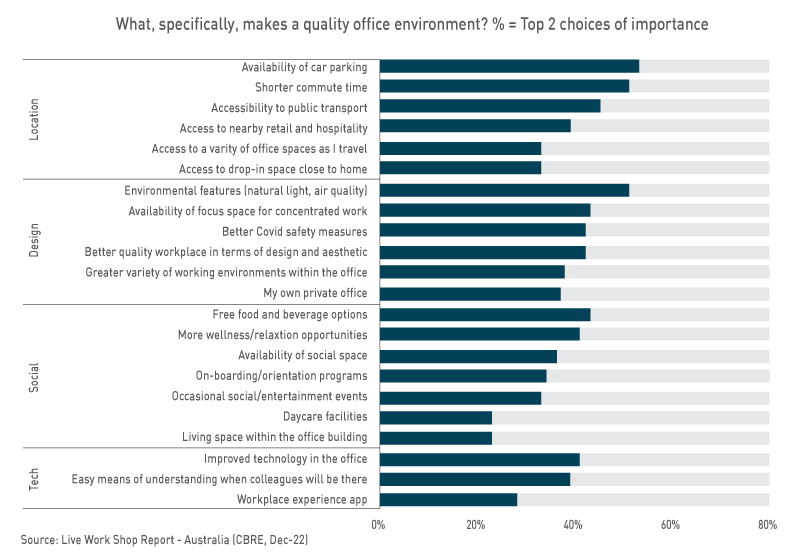

Conflating luxury with quality ignores the needs of many office occupiers. While the largest companies attract the most attention, most office-using Australian businesses are small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)4. With cost being the top driver of real estate decisions5, these SMEs are in the market for a Toyota, not a Rolls-Royce with all the extras. They want the highest quality office, in the best location, but within their price bracket. So then, what is “high quality” office? Ultimately, it’s space which meets the needs and preferences of its target occupiers.

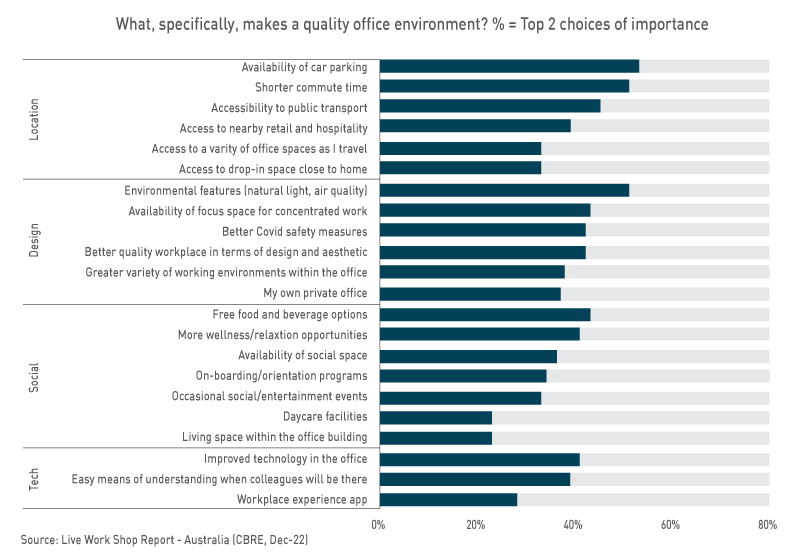

Some occupier preferences are timeless and will persist no matter how workstyles and space usage evolve, for example availability of natural light, convenient access to transport and plenty of nearby amenity (e.g. dining and gyms). These are hygiene factors valued by occupiers of any industry or size.

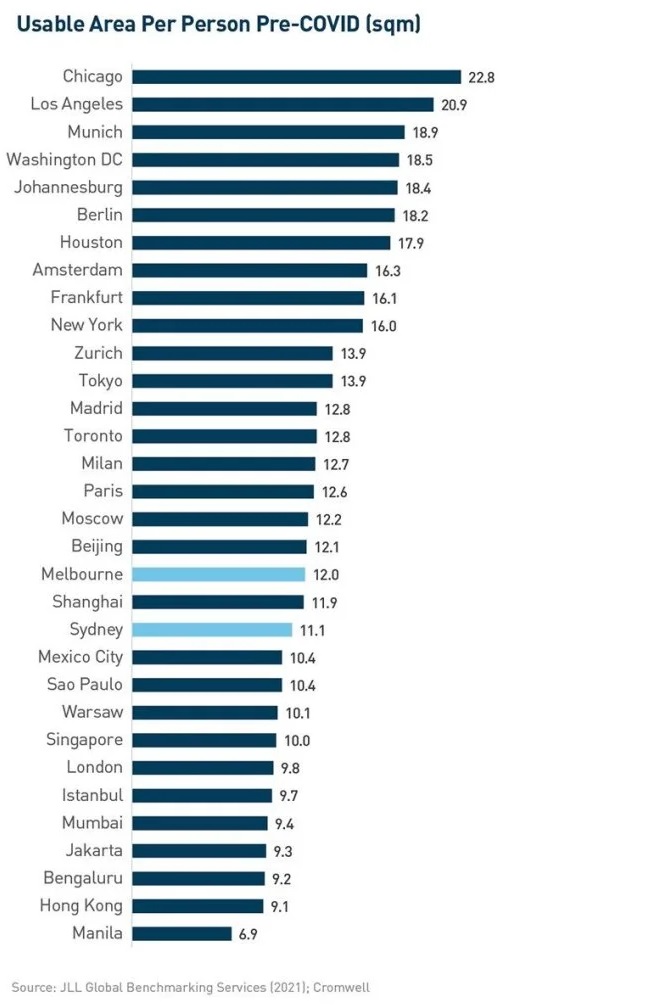

The pandemic has rendered some requirements less important. Floorplate size has historically been a measure of quality and is one of the criteria that determines whether a building is considered Premium or a lower grade. But with occupiers’ office usage shifting towards collaboration and social connectivity, a smaller floorplate can create more incidental interactions and a better ‘buzz’ in the office. While there is a minimum viable size in terms of efficiency and layout, we’re finding bigger isn’t always better in the eyes of occupiers.

Other requirements have increased in importance as occupiers shift to a new way of working. A greater level of embedded technology is expected, to ensure a flexible working model can be facilitated. Greater diversity of spaces is needed to support focused work, collaboration, and flexibility, with implications for building layouts and landlord-led fitouts.

Sustainability also continues to increase in importance, with a wider array of organisations focusing on both the financial and social benefits it can provide, including staff attraction and retention.

Greater diversity of spaces is needed to support focused work, collaboration, and flexibility, with implications for building layouts and landlord-led fitouts.

Not always the more sustainable choice

The preference for sustainable space is becoming more tangible and spans a variety of stakeholders, including end users, occupiers, and investors. Premium buildings often have the highest sustainability ratings (e.g. NABERS), something which is used to support the view that occupiers will increasingly gravitate to these assets over time. But again, these ratings don’t tell the whole story.

While new Premium assets are top performers from an operational emissions perspective (e.g. energy usage), production of building materials and construction activities are the largest producers of embodied carbon emissions6. As the grid decarbonises, embodied carbon’s share of built environment emissions is expected to increase from 16% in 2019 to 85% by 20506 – in the pursuit of net zero, minimising the demolition of existing buildings and the construction of new ones will become far more important than building-specific energy efficiency. As the importance of embodied carbon becomes more well known and stakeholders adopt a whole-of-life view of emissions, newly built Premium assets may not be considered the greener option.

Embodied carbon: the emissions generated during the manufacture, construction, maintenance and demolition of buildings – Green Building Council of Australia (GBCA)