How properties are valued

There are two main methods of valuation that are routinely applied to the asset valuations in Australia – the income capitalisation approach and the discounted cash flow approach. It should be noted that there are other methods of valuation, but, for the purposes of this article, we will examine these two most common methods.

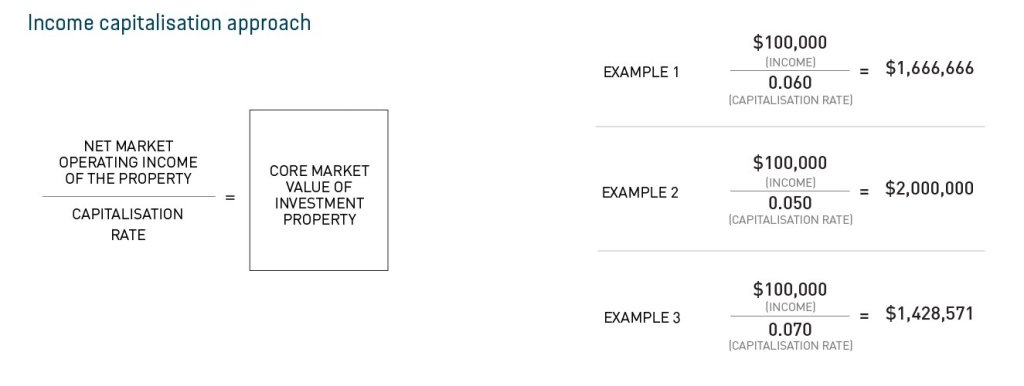

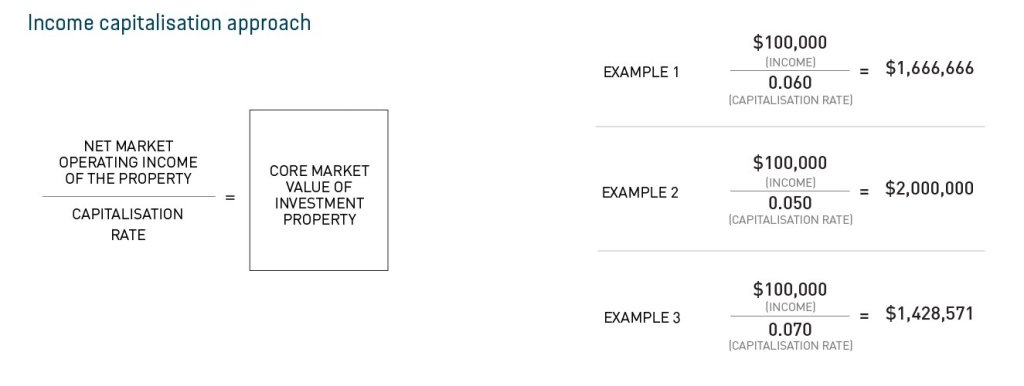

Income capitalisation approach

The income capitalisation approach to property valuation examines the net income a property would achieve in an open market – regardless of whether it is leased or vacant – divided by the appropriate capitalisation rate, to give the core value of the asset.

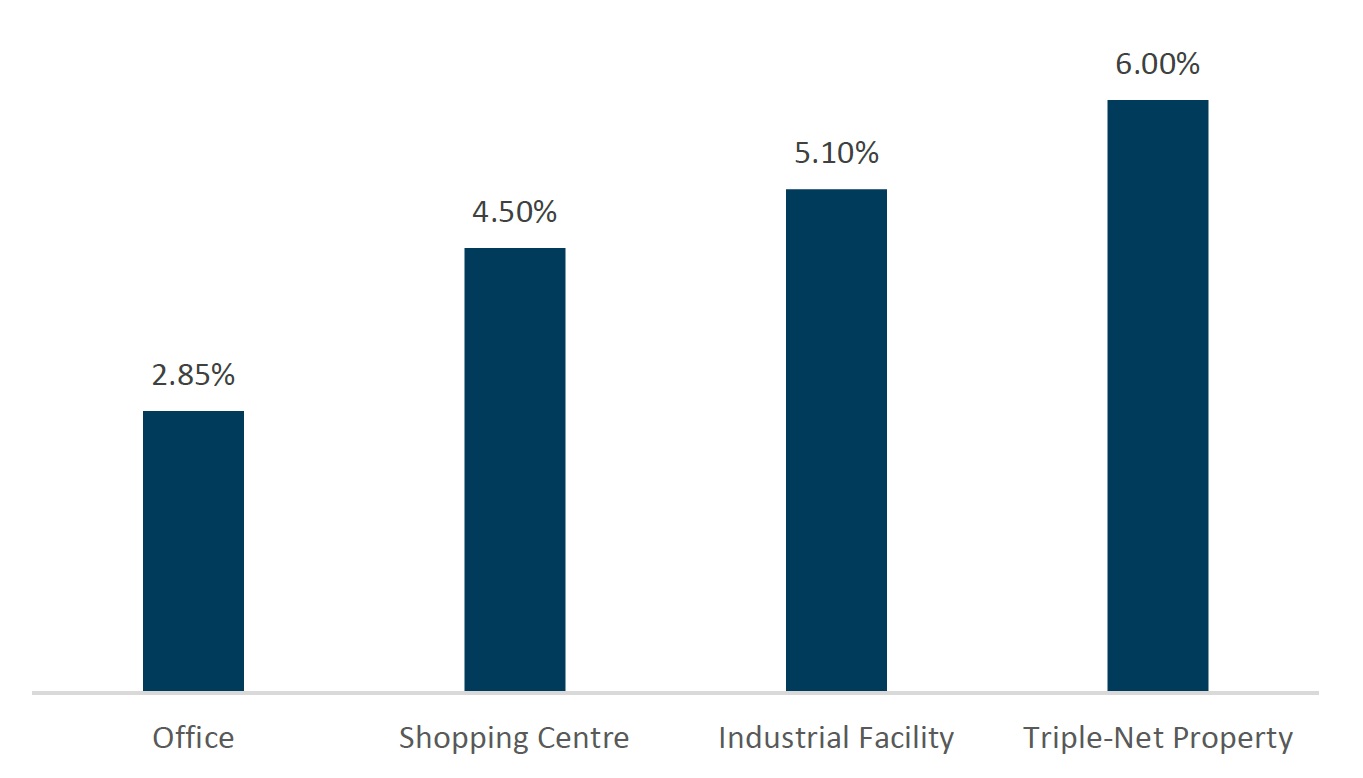

The capitalisation rate (cap rate) (yield) is the component that moves with market forces, such as interest rate changes, economic growth, vacancy rates, inflation, and lease covenants. The capitalisation rate is similar to the price-earnings multiple, often used when valuing shares. Valuers will also look at the capitalisation rates of comparable sales over the previous 12 months when calculating the market value of an asset.

In example 1 consider a property, which produces income of $100,000, is capitalised at 6.0% – the market value would be $1,666,666.

If, due to market forces, the capitalisation rate tightened to 5.0%, and the income remained the same, the market value of the property would increase as per example 2.

Example 3 demonstrates if the capitalisation rate rose to 7.0%, and the income remained the same, the capitalised value would decrease.

As you can see, market value moves inversely from capitalisation rates.

Once an asset value is determined, valuers can adjust for certain variables.

For instance, the valuers would make an adjustment for how much the current tenants are paying, compared to what the market rent of that property should be. Likewise, there would be adjustments made for any discount or tenant incentives that a building owner is applying to that space for the duration of those tenants’ leases.

As part of this approach, valuers also look forward over the immediate horizon – which might be anywhere between 12 and 36 months – to consider any near-term lease expiry and will make an adjustment to reflect the costs associated with that downtime and re-leasing. They will examine whether there is any vacant space, as well as the costs associated with leasing that space out.

Valuers also look at any capital expenditure (capex) considerations that there might be. For example, if there’s a broken lift, and it’s estimated that $5 million will be required for a replacement, adjustments will be made to the core value, to end up with the market value. That value is applied to a point in time – “as at” the day of valuation.

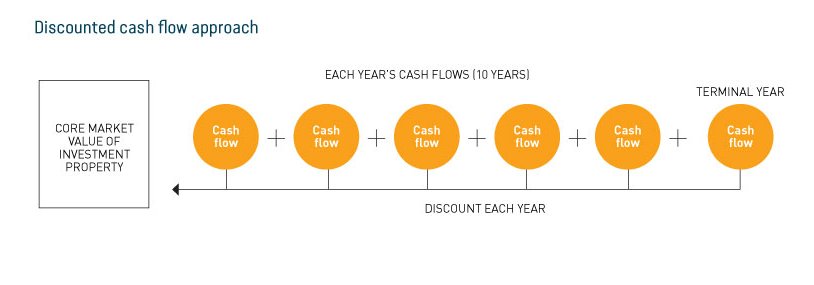

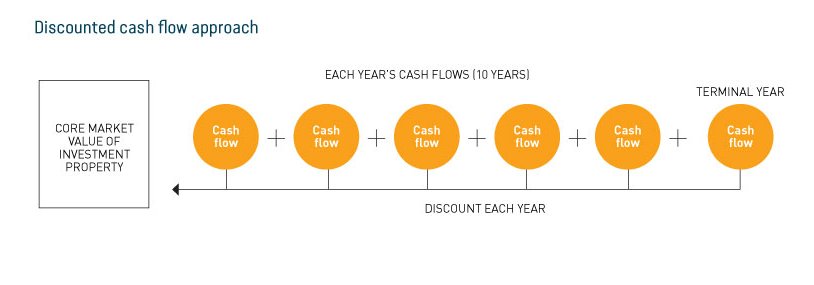

Discounted cash flow approach (DCF)

More assumptions are involved in a DCF when compared to the income capitalisation approach – including the target return or discount rate, rental growth, lease expiry allowances, renewal probability, capital expenditure, and a hypothetical sale profit– but it has the potential to provide a more accurate picture of the cash flow horizon over a longer period.

Using this method, valuers typically forecast a 10-year cash flow, with a hypothetical sale profit at the end of year 10. All the income over 10 years is discounted back to a present-day value at an appropriate discount rate. An exit terminal value at year 10 (for the hypothetical sale, using an appropriate terminal yield) is also discounted to a present-day value. To derive the net present value of the property, it becomes the sum of the discounted property cash flows and the discounted terminal value.

Determining an appropriate discount rate

To determine an appropriate discount rate, a comparison is made with returns from alternative investments, the most common comparison being the 10-year government bond rate, as it is considered ‘risk-free’ and matches the investment horizon. A premium is then applied to reflect the risk of a property investment when compared to the ‘risk-free’ rate.

Adjustments

Adjustments are made within the 10-year cashflow. For example, consider a multi-tenanted building. Realistically, not all tenants are going be there for the entirety of that 10-year horizon – so, these lease expiries are factored into existing lease cash flows.

The valuer considers what happens when each tenant’s lease expires, applying a renewal probability of that tenant remaining (or leaving) and applying associated costs for potential downtime, capex to refurbish the space and the costs associated with re-leasing (leasing fees, incentives, etc.).

If an expiry is in six years, for example, the valuer has an informed opinion of what the market rental should be as at today, and then they’ll apply a growth rate to get to the market rent at that point in time. They’ll also apply a tenant incentive and will have a hypothetical lease term at that point in time.

So, the valuer is making a lot more assumptions here than what they would do in a capitalisation approach – but they’re also getting a longer horizon of cashflows to look at.

Cromwell’s Investment Manager, Lachlan Stewart, is an experienced commercial real estate professional, who has spent more than 20 years working for highly respected organisations, including Colliers International and GE Capital Real Estate. He specialises in property valuations and financial modelling.

Cromwell’s Investment Manager, Lachlan Stewart, is an experienced commercial real estate professional, who has spent more than 20 years working for highly respected organisations, including Colliers International and GE Capital Real Estate. He specialises in property valuations and financial modelling.